Catholic Saints

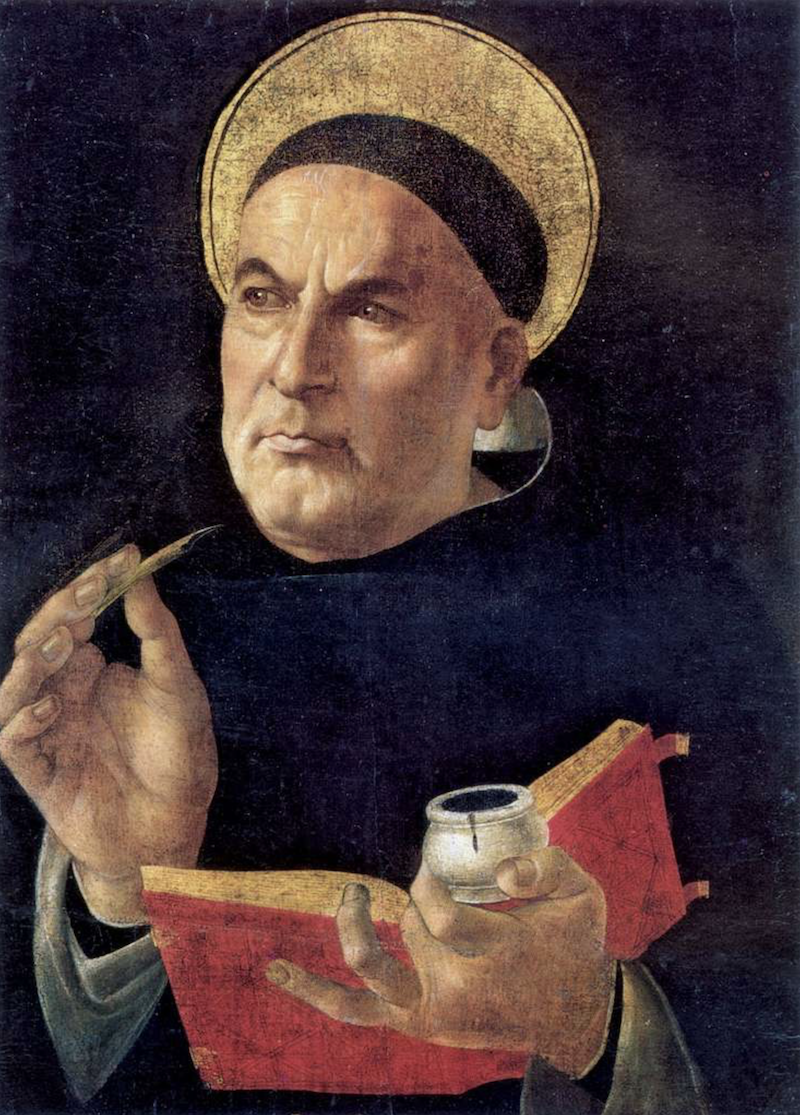

Saint Thomas Aquinas, born in 1225 in the small town of Roccasecca, Italy, emerged as a pivotal figure of the 13th century, renowned for his multifaceted roles as a Dominican friar, philosopher, and one of the most influential Doctors of the Church in Catholic history. His intellectual legacy is most prominently encapsulated in his monumental theological masterpiece, the Summa Theologica, a comprehensive work that sought to systematically address the deepest questions of faith, morality, and existence, cementing his reputation as a giant of medieval scholasticism. Aquinas spent much of his life teaching, engaging with students and scholars in prestigious centers of learning such as Paris and various cities across Italy, where his lectures and writings shaped the intellectual landscape of his time. His life came to an end on March 7, 1274, at Fossanova Abbey, yet his influence endured far beyond his death, as he was canonized in 1323 and later honored as a Doctor of the Church in 1567 by Pope Pius V.

His feast day is celebrated on January 28.

Doctor of the Church

Born in 1225 in Roccasecca, Italy, Aquinas became a towering figure in medieval theology and philosophy, leaving an indelible mark on the Church and Western thought.

Thomas Aquinas entered the world in a fortified castle in Roccasecca, a small village in the Kingdom of Sicily, as the youngest son of a prominent noble family led by his father, Landulf, a count, and his mother, Theodora, a woman of considerable influence. His early years were shaped by the expectations of his lineage, which destined him for a prestigious ecclesiastical career, specifically as a Benedictine monk at the nearby Monte Cassino abbey, a path that would have secured familial honor and influence. However, Thomas’s own aspirations diverged sharply from this plan when, at the age of 19 in 1244, he made the bold decision to join the newly founded Dominican Order, a mendicant group dedicated to preaching and study—a choice that sparked outrage among his relatives, who saw it as beneath his station. His family’s resistance was so fierce that his brothers kidnapped him and held him captive for nearly a year, hoping to dissuade him, yet Thomas remained steadfast, eventually escaping to pursue his calling.

His intellectual formation began in earnest at the University of Naples, where he encountered the works of Aristotle and developed a keen interest in philosophical inquiry, laying the groundwork for his later achievements. This education continued under the tutelage of Albertus Magnus, first in Cologne and then in Paris, where Thomas’s remarkable capacity for reasoning and his quiet, reflective nature earned him the nickname “Dumb Ox”—a playful jab from his peers that Albertus famously countered by predicting that this “ox” would one day bellow so loudly that his teachings would resound across the world. This period of study was transformative, as Thomas began to integrate classical philosophy with Christian doctrine, a synthesis that would define his scholarly career and distinguish him as a unique voice in the medieval intellectual tradition.

Aquinas’s early education and unwavering commitment to the Dominican Order forged a systematic approach that blended faith with rational inquiry, setting the stage for his monumental contributions.

After completing his initial studies, Thomas embarked on a teaching career that took him to the University of Paris in 1256, a hub of theological and philosophical discourse, where he assumed the role of a master of theology at an unusually young age. His time in Paris was marked by the production of significant works, including the Summa Contra Gentiles, a text designed to equip Christian missionaries with arguments against non-Christian philosophies, demonstrating his early concern for evangelization through reason. Returning to Italy later in his career, he continued to lecture and write, notably crafting the Summa Theologica, an ambitious project intended to serve as a comprehensive guide for students of theology, though it remained unfinished at his death. These writings delved into intricate topics such as the nature of God’s existence, the structure of human ethics, and the role of sacraments in salvation, often drawing inspiration from earlier thinkers like Saint Augustine, whose ideas on grace and divine order Aquinas adapted and expanded.

Among his most celebrated contributions during this period were the “Five Ways,” a series of logical arguments for God’s existence that utilized causality, motion, and contingency—concepts borrowed from Aristotle but reframed within a Christian context. These proofs not only showcased his ability to bridge faith and reason but also established him as a pivotal figure in shaping Catholic doctrine, offering a robust intellectual framework that countered skepticism and bolstered the Church’s teachings. His lectures, delivered with clarity and depth, attracted students and scholars alike, fostering a legacy of rigorous scholarship that resonated throughout medieval Europe.

Aquinas’s teaching career was a testament to his ability to combine meticulous scholarship with a profound spiritual depth that illuminated the mysteries of faith.

Throughout his tenure in Paris and Italy, Aquinas engaged with the pressing theological debates of his era, addressing challenges posed by secular philosophers and misinterpretations of Aristotelian thought that threatened Christian orthodoxy. His responses were characterized by a calm, methodical approach, as seen in works like De Ente et Essentia, where he explored the concepts of being and essence, providing a metaphysical foundation for understanding God and creation. His influence extended beyond academia, as he advised ecclesiastical leaders and participated in discussions that shaped Church policy, earning him recognition as a defender of doctrinal purity.

In 1567, centuries after his death, Pope Pius V officially declared him a Doctor of the Church, a title that acknowledged his enduring impact on Catholic theology and philosophy. His system of thought, known as Thomism, became a cornerstone of Catholic education, influencing seminaries and universities for generations. Aquinas’s ability to articulate complex ideas with clarity and precision made his works accessible to both scholars and laypeople, ensuring that his theological insights continued to resonate within the Church.

Aquinas’s unparalleled clarity in unifying philosophy and theology solidified his role as a protector of Christian truth against the intellectual currents of his time.

His efforts to counter secular and heretical ideas were not merely academic exercises but acts of faith, as he sought to demonstrate that reason and revelation were not in conflict but rather complementary paths to understanding divine reality. This is evident in his debates with contemporaries like Siger of Brabant, whose radical Aristotelianism challenged Church teachings, and in his careful refutations of errors that risked undermining the unity of Christian belief. Aquinas’s writings provided a bulwark against such challenges, offering a coherent vision that integrated human intellect with divine wisdom.

Aquinas’s life and works continue to serve as an enduring example of intellectual humility, spiritual devotion, and the pursuit of truth.

Thomas met his end on March 7, 1274, at Fossanova Abbey, a Cistercian monastery, while en route to the Council of Lyon, where he was to contribute to discussions on Church unity—an event his failing health prevented him from reaching. His death at the age of 49 marked the close of a prolific career, but his canonization in 1323 by Pope John XXII affirmed his sanctity, and his feast day of January 28 became a celebration of his contributions. With a corpus exceeding 60 works, including commentaries on Scripture and Aristotle, Aquinas left behind a treasure trove of wisdom that continues to guide Christian thought and practice.

Dubbed the “Angelic Doctor” for his purity of thought and serene disposition, Aquinas’s legacy lies in his demonstration that faith and reason are harmonious allies in the quest for God. His life of simplicity, prayer, and study, coupled with his refusal to let intellectual pride overshadow his devotion, offers a model for believers and thinkers across centuries. Today, his influence persists in Catholic theology, philosophy, and education, a testament to the timeless relevance of his insights.

Today, the Catholic Church commemorates his feast day on January 28, a date that serves as a testament to his enduring spiritual and intellectual contributions. Beyond his written works, Aquinas’s life was marked by a profound commitment to the Dominican Order, which he joined in 1244 despite fierce opposition from his noble family, who had envisioned a different path for him as a Benedictine monk. His education under luminaries like Albertus Magnus further honed his ability to synthesize Aristotelian philosophy with Christian doctrine, a synthesis that remains a cornerstone of Catholic theology. Known affectionately as the “Angelic Doctor,” Aquinas’s gentle demeanor belied the extraordinary depth of his intellect, earning him both admiration and the nickname “Dumb Ox” from his peers—a moniker that reflected his quiet nature rather than any lack of brilliance.

“To one who has faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without faith, no explanation is possible.”

Born in Roccasecca.

Born into a noble family in Roccasecca, Italy.

Began studies at Monte Cassino abbey.

Sent to study as a young child.

Studied at Naples.

Encountered Aristotle’s works.

Joined the Dominican Order despite family opposition.

Committed to a life of study and preaching.

Ordained as a priest.

Began serving as a Dominican priest.

Appointed master of theology at Paris.

Began influential academic career.

Wrote Summa Contra Gentiles.

Completed apologetic text for missionaries.

Started his theological masterpiece.

Launched extensive writing project.

Died at Fossanova.

Passed away en route to Council of Lyon.

“To one who has faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without faith, no explanation is possible.”

Saint Thomas Aquinas Quotes

“The things that we love tell us what we are.”

“There is nothing on this earth more to be prized than true friendship. It sweetens prosperity and lightens adversity.”

“Good can exist without evil, whereas evil cannot exist without good. For evil is a privation of good, not a substance in itself.”

“Wonder is the desire for knowledge. It arises when we encounter something greater than ourselves.”

“Law is nothing else than an ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has care of the community, and promulgated.”

“Grace does not destroy nature, but perfects it. It elevates what is human to participate in the divine.”

“The soul is like an uninhabited world that comes to life only when God sets up His dwelling there.”

“All that is true, by whomsoever it has been said, has its origin in the Spirit.”

“Man cannot live without joy; therefore, when he is deprived of true spiritual joys, he must become addicted to carnal pleasures.”

“The Eucharist is the sacrament of love; it signifies love, it produces love.”

“Fear is such a powerful emotion for humans that when we allow it to take us over, it drives compassion right out of our hearts.”

“Charity, by which God and neighbor are loved, is the most perfect friendship.”

“The knowledge of God is the cause of all things, for all things are known by God before they come to be.”

“Justice is a certain rectitude of mind whereby a man does what he ought to do in the circumstances confronting him.”

“Mercy without justice is the mother of dissolution; justice without mercy is cruelty.”

“The perfection of the human soul consists in knowledge of God above all things, and in love of Him above all things.”

“Hope is a virtue because it makes us look to God as the source of all good. It strengthens us to endure difficulties with confidence in His promises.”

“Faith has to do with things that are not seen and hope with things that are not at hand.”

“The human intellect, though it can know many things, cannot penetrate the essence of God. Yet it can know that He exists through His effects.”

“Prayer is the raising of one’s mind and heart to God or the requesting of good things from God.”

“God alone satisfies the deepest desires of the human heart. All other goods are but shadows of His goodness.”