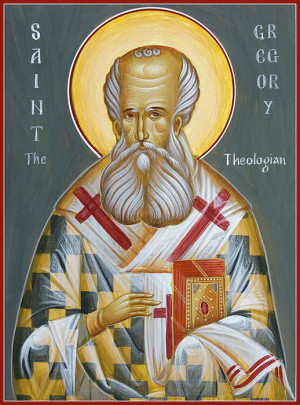

Catholic Saints

Saint Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329–390 AD), known as "The Theologian," was a fourth-century archbishop of Constantinople and one of the Cappadocian Fathers. Born in Arianzus, Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey), he was a key defender of Trinitarian doctrine against Arianism. A close friend of Saint Basil the Great, Gregory’s eloquent sermons and writings, including his Five Theological Orations, earned him lasting renown. Despite his reluctance for public office, his leadership during the Second Ecumenical Council (381 AD) helped shape orthodox Christianity. Celebrated on January 25 (or January 2 in the East), he is a Doctor of the Church.

His feast day is celebrated on January 25 in the West.

Cappadocian Father

Born around 329 AD in the small village of Arianzus in Cappadocia, Saint Gregory of Nazianzus rose to become a monumental figure in early Christian theology. His profound insights and eloquent defense of the Holy Trinity against heretical challenges left an indelible mark on the Church’s doctrinal foundation.

Gregory was nurtured in a deeply pious Christian household, where faith was a cornerstone of daily life. His father, Gregory the Elder, served as the bishop of Nazianzus, while his mother, Nonna, was revered for her saintly devotion and gentle wisdom. This environment shaped young Gregory’s spiritual outlook from an early age. His education took him to prestigious centers of learning—Caesarea in Cappadocia, Alexandria in Egypt, and finally Athens, the intellectual hub of the ancient world—where he honed his rhetorical skills and philosophical acumen alongside his lifelong friend, Basil the Great. Their bond, forged in the crucible of shared study and faith, would prove instrumental in their later efforts to defend orthodox Christianity.

Despite his intellectual gifts, Gregory initially yearned for the quiet simplicity of monastic life, seeking solitude to contemplate divine mysteries. However, his remarkable eloquence and sharp intellect soon drew him into the public sphere, thrusting him into ecclesiastical roles he accepted with reluctance but fulfilled with extraordinary dedication.

Gregory’s classical education, steeped in Greek philosophy and literature, combined seamlessly with his Christian upbringing to create a unique ability to express intricate theological concepts with both clarity and poetic grace. This synthesis of pagan learning and Christian faith enabled him to engage with the intellectual currents of his time while remaining firmly rooted in the teachings of the Church, preparing him for the monumental task of articulating and defending the doctrine of the Trinity.

Around 361 AD, Gregory was ordained a priest by his father, a role he accepted with hesitation due to his introverted nature. His ecclesiastical journey continued as he was appointed bishop of Sasima—a small, unappealing post he never fully embraced—before assisting his father in Nazianzus. His most significant role came in 380 AD when he was named archbishop of Constantinople, a city then embroiled in theological conflict. During the Arian controversy, which questioned the divinity of Christ, Gregory delivered his renowned Theological Orations, a series of sermons that showcased his rhetorical brilliance and theological depth.

In 381 AD, he presided over the Council of Constantinople, a pivotal gathering that reaffirmed the Nicene Creed and solidified Trinitarian orthodoxy. Despite his success, the political intrigue and personal exhaustion that followed led him to resign shortly after, retreating from the public stage to seek the peace he had long desired.

Gregory’s leadership during this turbulent period was instrumental in restoring the Church’s commitment to Trinitarian doctrine. His steadfast resolve and ability to navigate theological disputes amidst a fractured Christian community ensured that the orthodox understanding of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit prevailed against the Arian heresy, securing a legacy of doctrinal clarity for future generations.

Earning the title "The Theologian," Gregory’s Five Theological Orations stand as a masterpiece of Christian thought, offering a robust defense of the Trinity against Arian arguments that diminished Christ’s divine nature. These works, delivered with poetic flair, weave together profound spirituality and rhetorical artistry, reflecting his dual mastery of language and theology. Beyond the orations, his extensive sermons, letters, and poems reveal a mind attuned to both the mysteries of God and the beauty of expression.

Central to his theology was the balance of unity and distinction within the Godhead—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as one essence yet distinct persons. This framework profoundly influenced the Creed of Constantinople, a statement of faith still recited in Christian liturgies worldwide, cementing his role as a shaper of orthodoxy.

Gregory’s writings, rich with insight and enduring relevance, form a cornerstone of Christian theology. His ability to distill complex ideas into accessible teachings earned him the prestigious title of Doctor of the Church, a recognition of his lasting contributions to the intellectual and spiritual life of Christianity.

After stepping down from his role in Constantinople, Gregory returned to his native Nazianzus, where he embraced a quieter existence focused on prayer and writing. He spent his final years until his death in 390 AD compiling an extensive body of work—sermons, theological treatises, personal letters, and reflective poems—that preserved his voice as a champion of faith for posterity. His retreat was not an escape but a return to the contemplative life he had always cherished.

His legacy endures through his feast days—January 2 in the Western Church and January 25 in the Eastern tradition—where he is honored alongside Basil the Great and Gregory of Nyssa as one of the Cappadocian Fathers, a trio whose collective efforts fortified the theological foundations of Christianity.

Gregory’s theological clarity, coupled with his humble disposition, continues to inspire Christians across centuries. His life exemplifies a rare blend of intellectual rigor and spiritual depth, offering a model of faithfulness that resonates in modern times. His words and witness remain a guiding light for those seeking to understand the divine mysteries he so passionately defended.

“God is not a name but a reality… the fullness of being, the cause of all that is.”

Born in Arianzus, Cappadocia.

Born to a Christian family, Gregory studied in major intellectual centers.

Ordained a priest by his father, beginning his ecclesiastical career.

Became a priest.

Archbishop of Constantinople.

Delivered sermons defending the Trinity against Arianism.

Presided over the council, shaping the Nicene Creed.

Led Second Ecumenical Council.

Died in Nazianzus.

Left a rich theological legacy as a Doctor of the Church.

“Let us offer ourselves, the possession most precious to God, and most fitting; let us give back to the Image what is made after the Image.”

Saint Gregory of Nazianzus Quotes

"For nothing is so pleasant to men as talking of other people's business, especially under the influence of affection or hatred, which often almost entirely blinds us to the truth."

“Whoever does not accept Holy Mary as the Mother of God has no relation with the Godhead. Whoever says that he was channeled, as it were, through the Virgin but not formed within her divinely and humanly (“divinely” because without a husband, “humanly” because by law of conception) is likewise godless.”

“What was Adam? Something molded by God.31 What was Eve? A portion of that molded creation. Seth? He was the offspring of the pair. Are they not, in your view, the same thing—the molded creation, the portion, and the offspring? Yes, of course they are. Were they consubstantial? Yes, of course they were. It is agreed, then, that things with a different individual being can be of the same substance.”

“Discussion of theology is not for everyone, I tell you, not for everyone-it is no such inexpensive or effortless pursuit. Nor, I would add, is it for every occasion, or every audience; neither are all its aspects open to inquiry. It must be reserved for certain occasions, for certain audiences, and certain limits must be observed. It is not for all people, but only for those who have been tested and have found a sound footing in study, and, more importantly, have undergone, or at the very least are undergoing purification of body and soul”

“The Trinity is a single Godhead, not three gods, but one God in three persons, distinct yet undivided.”

“Let us reverence the silence of God, for even His silence is worthy of praise.”