The Catholic Church founded the first universities in the Middle Ages by evolving cathedral and monastic schools into formal institutions, such as the University of Bologna (1088) and the University of Paris (c. 1150), to educate clergy and laity in theology, law, and the liberal arts.

The Catholic Church founded the first universities in the Middle Ages by transforming cathedral and monastic schools into formal institutions of higher learning, beginning with the University of Bologna (1088) and the University of Paris (c. 1150), to educate clergy and laity in theology, law, and the liberal arts.

The Church sought to deepen understanding of faith through reason, preserve classical knowledge from Greece and Rome, and train clergy and administrators to serve both the Church and growing medieval society.

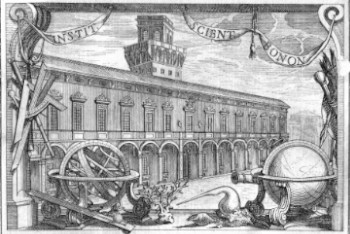

Early universities, such as Bologna and Paris, were communities of scholars and students organized under Church oversight, teaching subjects like theology, canon law, medicine, and the trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy).

They were typically governed by bishops or cathedral chapters, with masters and scholars (often clerics) forming guilds to regulate teaching, examinations, and the granting of degrees, under papal or royal charters.

Funding came from Church tithes, endowments by wealthy patrons, and papal support, supplemented by student fees, ensuring these institutions could thrive and expand across Europe.

Theology, dubbed the “queen of the sciences,” was central, guiding the curriculum and fostering scholasticism—a method of reconciling faith and reason—exemplified by figures like St. Thomas Aquinas.

The success of Bologna and Paris inspired the Church to establish or support universities in Oxford (c. 1167), Cambridge (1209), Salamanca (1218), and beyond, often with papal bulls granting them legitimacy and privileges.

While the Church set the overarching framework, especially for theology, universities enjoyed academic freedom in secular fields like law and medicine, fostering debate and inquiry within a Christian worldview.

They preserved and advanced knowledge, produced influential thinkers like Aquinas and Duns Scotus, and laid the groundwork for the Renaissance and modern science, shaping Western civilization.

Secular narratives often downplay the Church’s contributions to emphasize a supposed “dark” medieval past, ignoring how its universities bridged antiquity and modernity through faith-driven education.