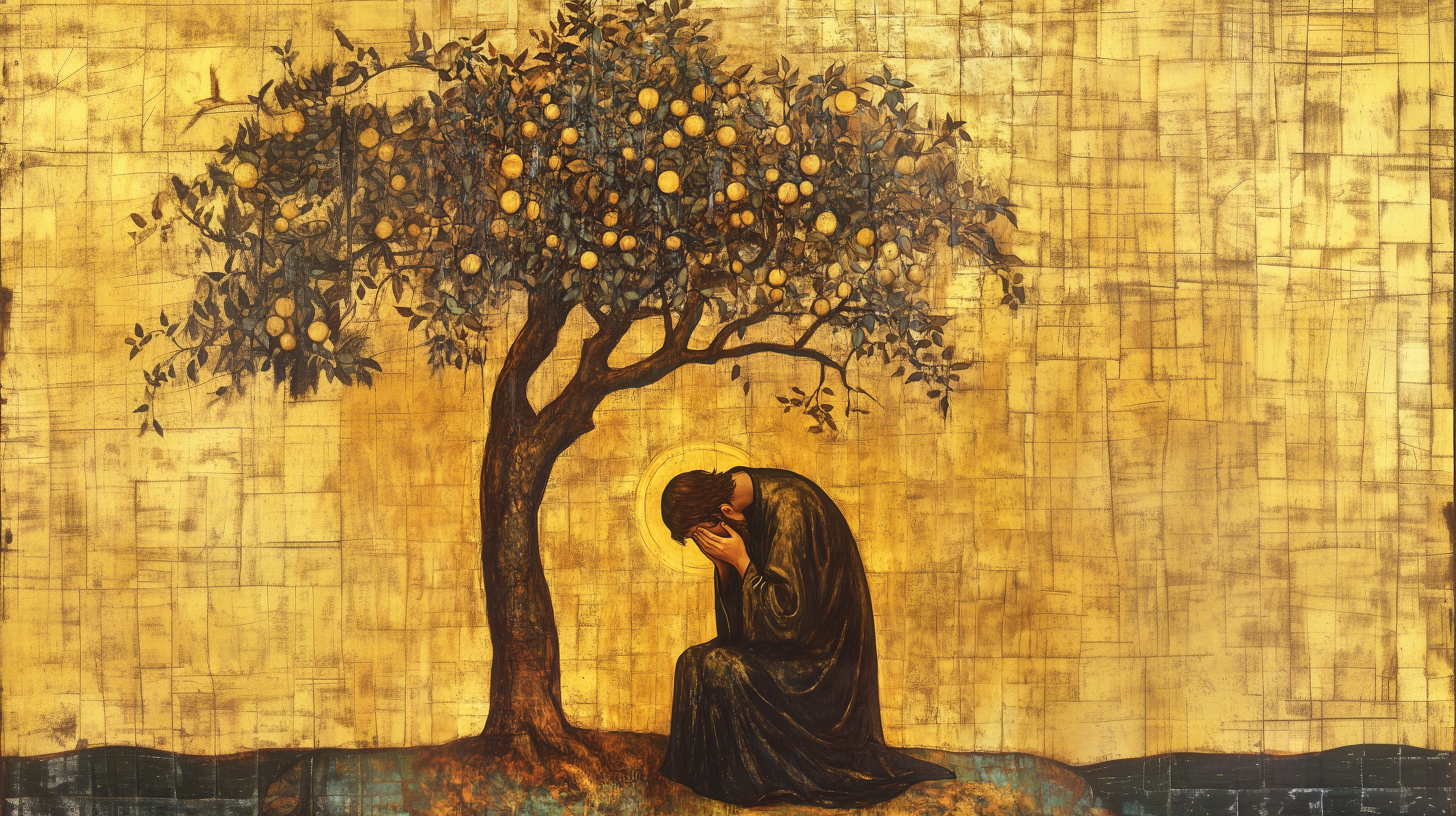

Recounted in Book II of Confessions, the Pear Tree Incident is a pivotal moment in St. Augustine’s youth, where he reflects on stealing pears not for hunger, but for the thrill of sin, revealing his early struggle with human nature and morality.

The Pear Tree Incident is a formative event from Augustine’s youth, detailed in Book II of Confessions. As a teenager, he and a group of friends stole pears from a neighbor’s tree in Thagaste, not because they were hungry, but simply for the pleasure of doing something wrong. Augustine later reflects on this act as a window into the human condition, revealing how sin can be enticing for its own sake. This moment stands out in his narrative as a stark example of his moral struggles before his conversion to Christianity.

Augustine confesses that his motive wasn’t hunger or necessity, as he had better pears at home, but rather the thrill of the forbidden act itself. He writes that he “loved the evil in me,” drawn by the excitement of sinning alongside his companions, whose company amplified his desire. This wasn’t about the fruit’s value—he discarded most of it—but about the perverse joy of rebellion. Looking back, he marvels at how this irrational choice reflected a deeper corruption within his soul, a theme he explores throughout Confessions.

The incident took place when Augustine was around 16 years old, circa 370 AD, in his hometown of Thagaste, North Africa. This was well before his conversion to Christianity in 386 AD, during a period of youthful recklessness and spiritual searching. He recounts it in Confessions, written between 397 and 400 AD, as a memory that haunted him into adulthood. The exact date isn’t specified, but its placement in his early life underscores its role as a prelude to his later transformation.

Augustine paints a vivid picture in Confessions, describing how he and his friends crept to the pear tree under cover of night, shook down the fruit, and carried it off. He notes they took far more than they could use, only to throw most of it to pigs, emphasizing the act’s pointlessness. His tone is introspective and remorseful, dissecting the episode with a mix of narrative detail and philosophical reflection. He uses this memory to probe the nature of sin, asking why he found such delight in an act so trivial yet so wrong.

Augustine admits he was driven not by need or desire for the pears, but by a twisted love for the sin itself—“I loved to perish,” he writes. He found a strange satisfaction in the act’s wickedness, heightened by the laughter and encouragement of his friends. Reflecting as an older man, he sees this as evidence of a heart drawn to evil for its own sake, not for any tangible gain. This self-analysis reveals his early awareness of human frailty, a cornerstone of his later theological work.

Augustine connects the pear theft to original sin, the inherited flaw that taints human nature since Adam’s fall. He argues that his senseless act mirrors humanity’s tendency to choose evil irrationally, even when good is within reach. This incident becomes a personal proof of the will’s corruption, a concept he elaborates in later works like City of God. For Augustine, it’s not just a youthful misdeed but a sign of a deeper, universal brokenness needing divine grace to heal.

Augustine explains that he and his friends discarded most of the pears or fed them to pigs, underscoring that the theft wasn’t about sustenance—they had no real use for the fruit. His family’s own pears were superior, making the act even more illogical. This wastefulness highlights his key insight: the appeal lay in the stealing, not the reward. He uses this to illustrate how sin often defies reason, driven by a perverse impulse rather than practical desire.

While he doesn’t quote Scripture directly in the pear tree passage, Augustine implicitly links it to Genesis 3, where Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit. He sees his theft as a parallel act of disobedience, choosing evil despite knowing better, echoing humanity’s first sin. Later in Confessions, he ties such behavior to Romans 7:19 (“I do not do the good I want”), reinforcing his point. This biblical undertone frames the incident as more than a personal failing—it’s a theological archetype.

Augustine emphasizes that he wouldn’t have stolen alone—the presence of his friends was crucial, their shared mischief fueling his resolve. He writes, “Alone I would not have done it,” suggesting the group’s laughter and daring egged him on. This social dynamic reveals how peer pressure can amplify sinful impulses, a point he finds troubling in hindsight. It’s a confession of weakness, showing how human connections can lead astray as easily as they can uplift.

The pear tree theft encapsulates Augustine’s turbulent teenage years, a time of restlessness, indulgence, and rebellion against authority. Living in Thagaste, he was a bright but wayward student, prone to seeking thrills over virtue, as he later admits with regret. This incident, alongside tales of carousing and theft, paints a picture of a young man adrift, far from the saint he’d become. It’s a snapshot of the raw material God would later shape through grace.

Augustine doesn’t mention any external punishment, like reprimands from his parents or the tree’s owner, suggesting the act went unnoticed or unaddressed at the time. The real consequence was internal—years later, he wrestled with profound guilt and shame over the memory. This self-inflicted penance drove his introspective writing in Confessions. It’s the spiritual weight, not a worldly penalty, that marked him and propelled his journey toward redemption.

Augustine freely chose to steal the pears, exercising his will, yet he later argues this freedom was enslaved to sin, not truly free to choose good. In Confessions, he ponders why he opted for evil when he could have refrained, hinting at a corrupted nature. This foreshadows his mature theology in On Grace and Free Will, where grace liberates the will from sin’s grip. The incident thus becomes a case study in his belief that human agency needs divine help to align with virtue.

Augustine learned that sin can be purposeless, a revelation that struck him as he pondered the pears’ worthlessness to him. He saw his actions as evidence of a heart drawn to evil irrationally, a discovery that deepened his understanding of human nature. This insight fueled his later conviction that only God’s grace could redirect such a wayward will. It was a humbling lesson in his dependence on divine mercy, shaping his spiritual awakening.

Writing decades later, Augustine dissects his guilt with striking candor, questioning why he delighted in the theft and what it revealed about his soul. He sees it as a symptom of a deeper malaise—sin’s hold over him—beyond mere youthful folly. His analysis is both personal and universal, asking God, “What was it that I loved in that theft?” This self-scrutiny transforms a petty crime into a profound meditation on human fallenness and the need for redemption.

Augustine includes the pear tree story to bare his soul before God and readers, confessing even seemingly minor sins to highlight their spiritual weight. It’s a teaching tool, showing how small acts can reflect humanity’s broader moral struggles. By sharing this, he invites others to examine their own hearts, making it a universal lesson in humility. It also underscores God’s mercy, which reached him despite such beginnings.

The lingering guilt from the pear theft hints at Augustine’s growing discomfort with his sinful life, a restlessness that built toward his conversion in 386 AD. It shows a young man aware of his flaws yet unable to escape them, setting the stage for his dramatic encounter with God in Milan. This early unease with sin’s emptiness made him receptive to the grace that later transformed him. It’s a quiet prelude to the famous “Take and read” moment that changed his life.

The passage blends vivid storytelling with deep introspection, a signature of Augustine’s confessional style in Confessions. He narrates the theft with sensory detail—night, pears, pigs—then shifts to probing questions about his soul, addressing God directly. This mix of memoir and meditation makes it gripping and thought-provoking. It’s less a dry recounting than a living dialogue with his past and his Creator.

Augustine comes to see sin as a perverse love of evil for its own sake, not just a breach of rules, as the pear theft showed him. He realizes it’s often motiveless, a distortion of human desires that seeks destruction over creation. This shapes his later theology: sin is a sickness of the will, curable only by God’s grace. The incident thus becomes a cornerstone in his understanding of humanity’s spiritual plight.

The pear tree incident is famous for its raw honesty—Augustine’s willingness to expose a petty yet revealing sin captivates readers. Its depth lies in how he transforms a minor act into a profound commentary on human nature, making it relatable across time. Scholars and believers alike cite it as a classic example of self-awareness and moral reflection. Its enduring appeal stems from its simplicity paired with its theological richness.

The pear tree story bolstered Augustine’s legacy as a thinker who laid bare his flaws, influencing Christian psychology and ethics for centuries. It showed his ability to find universal truth in personal failure, inspiring figures like Aquinas and later theologians. His candidness made Confessions a timeless work, cementing his role as a father of Western Christianity. This incident, small yet monumental, underscores why he remains a giant in religious thought.

One of the greatest minds in Western Civilization was once a rebel—a womanizer & a thief. He was a proud man seeking fame & approval. Yet, the sinner turned saint changed not just himself, but history. What Augustine's "Pear Tree" incident can teach us about ourselves.